In Nepal’s Far West, pig and vegetable farming is the main source of livelihood for former bonded labourers

Former bonded labourers in Nepal’s Far Western Region earn a modest living by raising pigs and growing vegetables. FCA offers support to local people to help them earn a living, but in the most impoverished villages severe drought and all-engulfing fires make life extremely challenging.

IN A NORMAL summer, the Mohana River floods across the flat terrain all the way to the village of Bipatpur. Taking vegetables across the river to India would require a boat and a skipper.

In Nepal’s Far West, the annual monsoon season usually starts in early June, but this year the rains were weeks late. For local women, crossing the border from Nepal to India seems fairly easy; all they have to do is lift up their saris, roll up their trouser legs and wade across the river. It has been scorching hot for nearly two weeks now, with temperature rising above 40 degrees.

The ground is parched, and plants and people are desperate for water. Some of the wells in the village have dried up and there is no point in looking for new ones because finding groundwater is too uncertain and the costs of digging too high.

This has been an exceptional year in more ways than one. This spring, following a disaster in April that destroyed the harvest and stores, the women of Bipatpur had nothing to sell to the Indian vegetable markets across the river.

“Only people were saved”

Burning crop residue on the fields to release nutrients is an annual tradition in Bipatpur. This year, an unpredictable and exceptionally strong wind caused the fire to spread quickly and uncontrollably. Houses, food containers, and livestock shelters burned down one after another. The fire destroyed or damaged the homes of 71 families and killed domestic animals.

Villagers cleared away the charred tree trunks, but the sad and disheartened feelings remain.

“Only people were saved,” the women say.

The fire also engulfed a large chunk of the village cooperative’s savings, which were kept in a box. Belmati Devi Chaudhary, 42, looks at the charred remains of her house.

“Everything is gone. All we have is emergency aid.”

A sow the family had bought with financial support from Finn Church Aid died in the fire. Without a mother to care for them, five piglets died, too. This was a huge loss for the Chaudhary family.

The money Belmati Devi Chaudhary had earned from pig farming helped her to pay for her children’s schooling. Standing next to his mother, the family’s eldest son Sanjay Chaudhary, 23, looks helpless.

“I may have to go to Kathmandu to find work. It’s difficult to get a paid job here,” he says.

For many years, scores of young Nepalese men have left for the capital city or for India in search of odd jobs, but Belmati doesn’t want her son to follow in their footsteps.

Like many others in Bipatpur and in the surrounding Kailali District, the Chaudhary family are former bonded labourers. Although Nepal’s 200-year-old Haliya and Kamayia bonded labour systems were abolished in the early 2000s, many former bonded labourers and their descendants are still very vulnerable.

Sustainable livelihood with pig farming

Jumani Chaudhary, 50, is one of 29 women in a group supported by FCA. These women run a pig farm in the municipality of Gauriganga. They have learned how to make porridge for pigs from corn and wheat milling byproducts.

“By feeding pigs porridge, we save on feeding costs, and the pigs are healthier and grow faster,” Jumani Chaudhary says.

The women plan to start selling their pig feed to other pig farmers. To safeguard feed production, they would like to set up their own mill.

In a pig pen, three different-coloured pigs oink and jostle for food. Sows are less than a year old when they produce their first litter. Typically they can produce two litters a year, around ten piglets each time. With the right care and nutrition, pigs grow quickly.

“A full-grown boar is worth up to 30,000 rupees,” says Bishni Chaudhary, 43.

Sanu Chaudhary, 27, who lives next door and is also a member of the women’s group, says she recently sold seven pigs for 50,000 rupees. Converted to euros, the sums seem somewhat modest: a thousand rupees equals roughly seven euros. But in the Far Western Region of Nepal, this money goes a long way. You can buy a school uniform for your child, meals for the entire school year, a water bottle and school supplies.

“Pig farming is easier and requires less work than buffalo farming. Buffaloes only produce milk part of the year, when they nurse their calves,” Jumani Chaudhary explains.

When buffaloes don’t produce milk, they produce nothing, but cost ten times the price of a pig.

“Before, we had to beg for food”

The road further west to the Dadeldhura district twists and turns along the lush green hills. Compared to the flat terrains of Kailali, Dadeldhura is topographically much more uneven. The winding road barely fits our car, giving the scenic drive an extra twist. Finally, we arrive in the village of Ganyapdhura.

We can see hints of green on the terraced farms even though the rains are late. The Dalit community living here grows cauliflower, potatoes and zucchini. Growing vegetables is more than a livelihood; it has given the community a sense of value.

“Before, we had to beg for food, but now we grow vegetables for sale,” says Gita Devi Sarki, 38.

In 2019, Finn Church Aid helped the community further improve its farming efficiency by supporting the Sarki family and 24 other local farmers in the introduction of tunnel farming. The plastic cover of the tunnel protects the vegetables from the elements and retains moisture. The community also received a walk-behind tractor, which makes plowing much easier. Gita Devi Sarki is the only woman who knows how to operate the machine – and even she needs her husband’s help to start it.

“Before, our farm was just big enough to produce corn and wheat for our own family. Now we can save 410 rupees each month by selling some of the vegetables we grow,” she says.

Most importantly, having a more secure livelihood meant that Gita’s husband Padam Bahadur Sarki, 42, was able to return home from India, where he worked for twenty years. The couple have been together for 22 years and have four children. Almost all this time, Gita Devi Sarki was in charge of the family’s day-to-day life, alone.

“I returned to Nepal due to the COVID-19 lockdowns,” he says.

“It’s a good thing you came back,” Gita Devi Sarki says, with a grin.

“Yeah, it’s been OK,” her husband replies, causing the group of women sitting around him to burst into laughter.

Having her husband back has reduced Gita Devi Sarki’s workload in the farms. The family plans to expand their business to raising goats and small-scale fish farming in a small pond in the valley.

From bonded labourer to a member of a local government

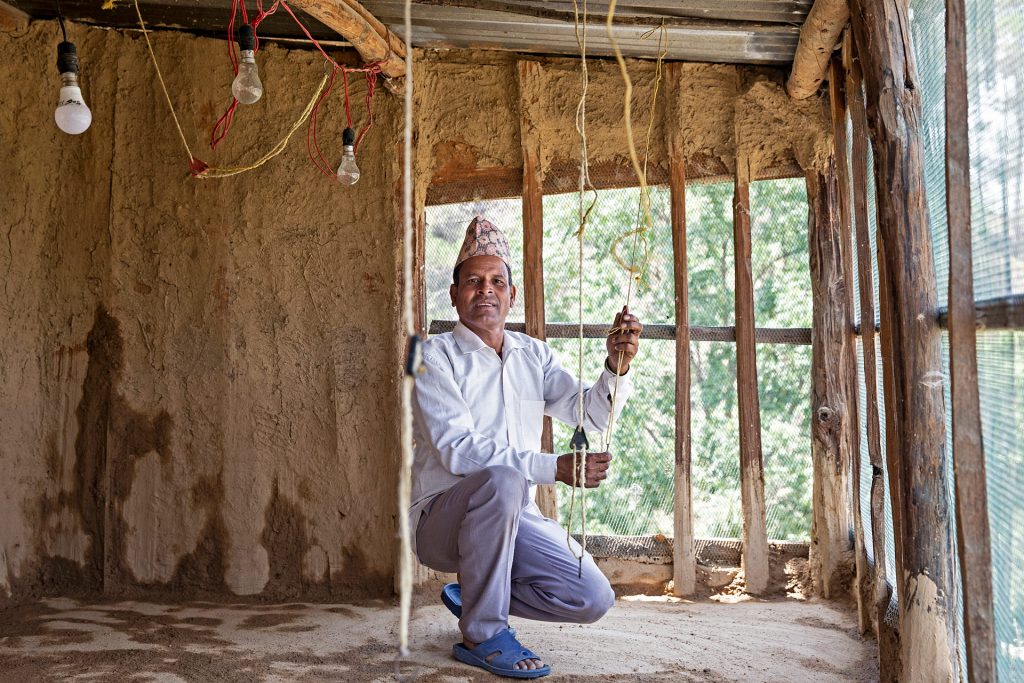

A pretty little house has a downstairs door open, and a wide-eyed cow peeks through the door. Bahadur Damai, 52, beckons to visitors to join him in the shade under a canopy. Back in the early 2000s, before the abolition of the Haliya system, he was a bonded labourer, mending other people’s clothing. Today, he smiles happily as he talks to us about his chickens and a small tailor’s shop he has opened in a nearby village centre.

Money has given his family a more stable livelihood, allowing him to buy things like a television. He has also been able to pay for the weddings of his two adult daughters, something that clearly makes him very proud.

One of his greatest achievements, however, was being elected a member of the local government in May.

“It’s all thanks to FCA that I am where I am now. I received support for vegetable and chicken farming, and I’ve been able to build relationships that won me votes in the election.”

He pauses mid-sentence when a gust of wind tries to rip off the chicken coop’s corrugated iron roof. Bahadur Damai gestures at his son, telling him to put big stones on the roof to keep it in place.

“A new chicken coop would be nice,” he says. Suddenly he becomes serious.

“You know, my wife and I only have one significant difference: she has aged faster.”

The look on his face says this is not a joke.

“Women age faster here because their lives are so much harder that men’s. It is a local tradition that women eat after everyone else, whatever is left. Pregnancies, childbirths, hard physical labour…As an elected member of the local government, I intend to raise awareness of the problems women have in our communities, such as the disproportionate burden of domestic work and domestic violence,” Bahadur Damai says.

But that’s not the only thing he wants to draw attention to. In this district, former bonded labourers are still not eligible for the Nepali government rehabilitation programme, which promises them land ownership, education for children, and employment opportunities for young people.

Bank accounts secure the future

In Bipatpur, the village women have gathered together under a canopy. In fact, this used to be a house, one of the women points out. The charred roof beams have been removed and replaced with new ones. At noon, the sun is beating down, and the temperature in the shade is approaching forty degrees. It turns out that the name of the village, Bipatpur, means disaster in the local language. This village has certainly had its fair share of disasters, from floods to fires.

But perhaps today things will take a turn for the better. Representatives of the local government and the bank will be visiting the village. With support from FCA, every family that lost their house in the spring fire will receive a humanitarian cash transfer. For those whose homes were damaged to some degree, 13,500 rupees, or about 106 euros, will be offered for reconstruction, and those who suffered the greatest losses will receive 34,500 rupees, or 270 euros. Pregnant women, nursing mothers, families and the elderly will receive an additional 500 rupees.

For the first time, cash transfers will be paid to women’s own bank accounts. This ensures that their money is safe, and that even if another disaster strikes the village, not all of their possessions will be gone.

Text: Elisa Rimaila

Photos: Uma Bista

Translation: Leni Vapaavuori

Finn Church Aid has had a country office in Nepal since 2013. Our work focuses on providing income opportunities for former bonded labourers, on ensuring the realisation of their rights, and on improving women’s livelihoods. After the earthquake in 2015, we built safe school facilities for 44,000 children, trained teachers and supported mental recovery. In 2021, we took action to alleviate the food insecurity affecting nearly 18,000 people as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.