Nearly 100 child soldiers into professional education in Congo

“How many of you have fought in the armed groups?” asks Marc Balekage in an education centre for former child soldiers in Eastern Congo (DRC). Five slim hands are immediately raised.

“You can answer truthfully. In here it is neither a fault nor an obstacle for anything. This place is for you”, Balekage reassures the young.

Around 25 hands are raised.

This happens during a registration session for the class of 2015 in an ETN centre maintained by Finn Church Aid. The one year professional education is directed at young people who previously have had no possibilities for education. Orphans, sexually assaulted women and young single mothers are enrolled on the courses alongside former child soldiers.

110 students between the ages of 15 and 23 have been accepted for the class beginning in late January. Today, the first 60 are meant to come in for registration.

Around 30 boys and some girls are present in the early hours of the morning. Slowly the young wander into the classroom. Many have made their way on foot from tens of kilometres away, so being late by an hour or two is not worth noticing.

The battleground begins at the school yard

The ETN education centre has been working in the small town of Masisi, in the poor and unstable province of North Kivu for two years. Even though no armed conflict has been fought here for two years, seven different armed groups reside in the breathtakingly beautiful hills around Masisi.

They mainly fight against each other and the Congo army. The presence of armed groups makes agriculture on the hills highly risky. People are used to moving away quickly and often.

“You mustn’t think whether the nearest group is ten or thirty kilometres away. The closest combatants are always right here, outside our gates”, Marc Balekage says in the yard of the ETN centre.

“All the young people who pass through here know how to use a weapon. Very many carry a weapon with them. Here, we try to show that answering violence with violence is not the solution”, he continues.

Tumaini Mongali selling various products in Masisi. She has received support from the Women’s Bank to start her business and she has received education at the ETN centre. Photo: Ville Asikainen.

A change to have a profession lures out of the forest

The class of 2015 begins Monday, January 26th. Some of the participants were still with the armed groups in the jungle in December. The possibility to gain a profession has motivated some to leave their weapons and separate from the armed groups.

“I saw a carpenter near my home town. He had graduated from the ETN centre a year ago. He was called an engineer and he had many job offers available to him. I figured that I want to become like him”, says Isac, 18, who has come to register.

He has been a fighter with the group Mai Mai since 2011. He didn’t leave the group until December.

“I spent New Year’s at home for the first time in a long time. My mother and father are both dead, so I couldn’t celebrate New Year’s with them anymore.”

Isac left the Mai Mai armed group last December. Now he has come to register for professional education. Photo: Ville Asikainen.

Mason is the most sought profession

The ETN centre offers three branches for professional education: masonry, carpentry and cooking.

Most of the young sitting in class now, hope to study the craft of mason. Being a cook feels strange. No one answers, when the director of the centre, David Ngabo, asks if the young know the kind of work a cook can do.

“Students from last year’s class got work in fine hotels all the way in Goma”, Ngabo reassures.

Entrepreneurship and customer service are a part of common studies for everyone. The first two hours of every morning are given to learning how to read and write. Some of the young have spent their entire childhood and adolescence in the woods. Not everyone can even write their own name.

Combatant: a profession like any other

Becoming a combatant is a very natural option for many young people in North Kivu. For many, their families have been forced to run away from the fighting many times. There isn’t enough money for food, let alone school fees. Poverty limits the available options.

In addition, the youth of Masisi have grown up in the shadow of violence. Conflicts in the area have raged for decades. The Rwandan genocide and the refugees created by it were followed to the region by another war, one that never really ended. Every day, young people can be seen walking around with Kalashnikovs in their hands.

Many who have become fighters come to be disappointed by their choice. “Ordinary soldiers don’t get paid. They can be happy to get some food”, explains one of the school teachers, Heritier Nguma, himself a former child soldier.

“I was a soldier for three years. All the money went to the officers.”

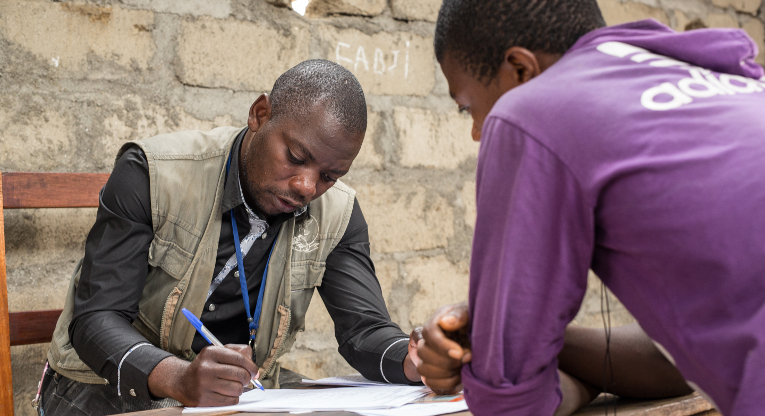

ETN employee David Ngabo taking registrations from new students at the Masisi education centre. Photo: Ville Asikainen.

Students are found by circling the villages

Even if the career of a soldier doesn’t amount to the expectations, abandoning an old way of living is difficult for many. Enrolling in studies is a tall order.

“We ask priests to spread information on our educational opportunities in churches and police officers and officials in their areas. Graduated students also recommend new students for us. Most of our recruiting, however, is based on us going around the villages talking to people. That way we come to know who might be interested in studying”, Ngabo explains.

Around Masisi, the young people who have left their armed groups are in constant danger. Many are recognized as combatants, and the surrounding community shuns and even fears them. Others might be hunted by their former groups that try to get them back in their ranks.

“The problem last year was that large groups of young people caused fear. Such groups might have been considered as new fighting forces. That’s why we got school uniforms and ID cards for all our students proving that they are participating in our program and have laid down their arms”, Ngabo tells.

A big decision

Both men and women fight for the armed groups of North Kivu. The groups don’t care about gender differences. David Ngabo and Marc Balekage are hoping that this year more than half of the students would be girls. But after two hours of registration, only a few have come by.

Then the crowd outside the door stirs. A small, doll-faced and very pale girl is standing outside the centre.

“He has been a fighter for the Mai Mai group for five years. Her rank is major”, Balekage says.

The serious looking girl tells that she has come to register. She doesn’t yet step in the door thought.

As we leave, the girl still stands in front of the ETN centre.

She has a big decision to make.

Finn Church Aid is funding ETN education centres in Masisi and Goma. Approximately 385 children are studying in them. Most of the students are former combatants. In 2014, approximately 40 % of students were female. In 2015, the goal is 60 %. FCA supports the centres with 100 000 euros annually.

Text: Satu Helin