Finn Church Aid makes sure that in Adjumani inclusive means everybody

The Adjumani district lies in the north of Uganda, a stone’s throw away from the troubles of South Sudan. It is here where you will find the largest population of South Sudanese refugees, fleeing murder, rape and unconscionable cruelty where even the disabled have been reported to have been burnt alive. However, crossing the border into the relative safety of northern Uganda does not spell the end of the journey for many of these families – especially those that are also caring for disabled children.

Chawich is a delightful, bright eyed boy who dreams of getting an education. His infectious smile drops away when asked why he left South Sudan. “I saw many dead bodies”, he whispers.

Chawich and his mother outside their tuku hut. Chawich’s wish of an education will finally be realised in the Inclusive Education facility funded bv FCA.

Chawich cannot use his legs and moves around on the dusty ground by crawling on his hands and knees. The years of crawling and scraping on rough ground have left their mark on his knees, which appear sheared, flattened like a table top, the skin roughened as sand paper. “I’m not happy. I’d like to be taken to school to study”, he says.

The tragedy here is not just seeing a young boy being denied what is a basic human right in education, but witnessing the devastation war has caused to thousands of families just like Chawich’s. Can you imagine fleeing war only to find yourself in a foreign country with limited support to care for a disabled child?

“I valued his life most and gave him all my attention out of all my children because he was disabled and there was no one to help him”, says Chawich’s mother.

Chawich’s mother was forced to make a heart breaking decision when fighting intensified in her village and she was forced to flee. Panicked, gathering her other children and few belongings, she was faced with the near impossible decision of whether to carry her elderly mother or Chawich. She chose to take Chawich knowing full well what his fate would have been had he been left behind.

War robbed him of an early education, and it was looking like his disability would confine him to the fringes of the refugee settlement. There is a school in the settlement, but not close enough for it to be accessible for children like Chawich. Every day, Chawich watches his elder and younger brothers collect their books and leave for school.

Thousands in need of special needs education

According to UNICEF there are 3,000 to 4,000 children with a disability living in Adjumani. And that’s just the ones that have been reported. The stigma of having a disabled relative often makes those afflicted invisible. They disappear from the public gaze to stymie the judgement that can accompany their family, carers and themselves.

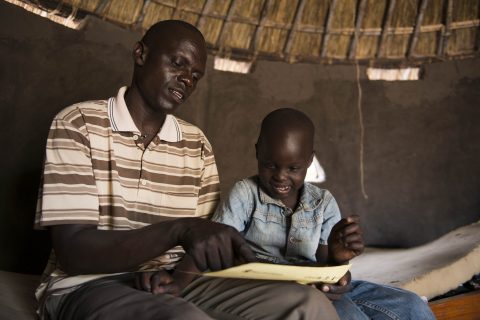

Thesame and his father John inside their tuku at a refugee settlement in Adjumani.

In one refugee village in Adjumani, there were five children with disabilities ranging from Down syndrome, to developmentally delayed, to severely disabled and requiring 24-hour care. One young boy, Thesame, 7, is hearing impaired and developmentally delayed. His family communicates with him using a unique sign language they have developed together.

“I realised Thesame couldn’t speak at an age when he should have been speaking, and this was painful for us. You don’t expect your own child to be deaf-mute”, says John, Thesame’s father.

“He needs to be taken to a school where the teachers are specialists in handling children with disabilities, and I know he will adapt easily there.”

New resources for inclusive education

In 2015, Finn Church Aid trained 75 teachers in Adjumani in Inclusive Education to help children like Chawich and Thesame.

“It is very important for refugee children to get attention. Because of the war most of the children have not gone to school. But now they have that opportunity. Those who are disabled can get educated”, says Aliku, who is a devoted teacher and now one of the first Inclusive Education teachers to take up a position at the Pakele Primary School. The new facility, funded by Finn Church Aid and its partners, opens its doors to children with disabilities from both host and refugee communities, bringing enormous relief to both the children and their families.

Christine chats with Aliku during an athletics carnival at Pakele Primary School.

Aliku explains that inclusive education models do more than educate, they build self-esteem. “Inclusive means everybody”, Aliku says. “It is very important for them to feel like other children, so we have to ensure they are given all they need.” Aliku now has the capacity to identify children’s needs and accommodate them in his classroom.

Whether they are epileptic, hyperactive, developmentally delayed, hearing or vision impaired, Aliku now has the skills and resources to make sure that none of his students are left behind.

“I will be able to help myself. This makes me happy,” says 16-year-old Christine, a young woman from the host community who is confined to a wheelchair. The construction of specially designed dormitories will mean she no longer has to make the dangerous journey from her sister’s house to school each morning. The fumes of dust from passing trucks and cars make the road almost impossible to see, and the rutted, graded road is exhausting to navigate in her wheelchair. The perilous roads are not the only hurdle for children like Christine however.

“It is good to get to that school, where I can freely associate with other children like me without being mocked”, she says.

Classrooms are accessible by wheelchair and brightly lit to help the visually impaired. Toilet facilities have also been constructed with ramps and rails.

New beginning for the children

FCA’s classrooms are built with ramps and enough space for wheelchairs.

It is the first day of school for the kids at the Pakele Primary School and there is nervous apprehension in the air. We joke and play with the children to ease their nerves, but it is in the classroom where we see them really settle.

Aliku starts his class by getting the children to repeat the days of the week. Chawich sits in the front row, in a new and foreign space, with other able-bodied children. But if he was shy or awkward, you wouldn’t guess it. “Monday! Tuesday!” he yells like he is running for office. Chawich sets the classroom alight with such enthusiasm and gusto it is hard to imagine other 16-year-olds anywhere in the world taking such delight in learning.

Chawich, Christine and Thesame shouldn’t have to fight for education, since it is their right.

Text, photos and video: Hugh Rutherford