What is resilience?

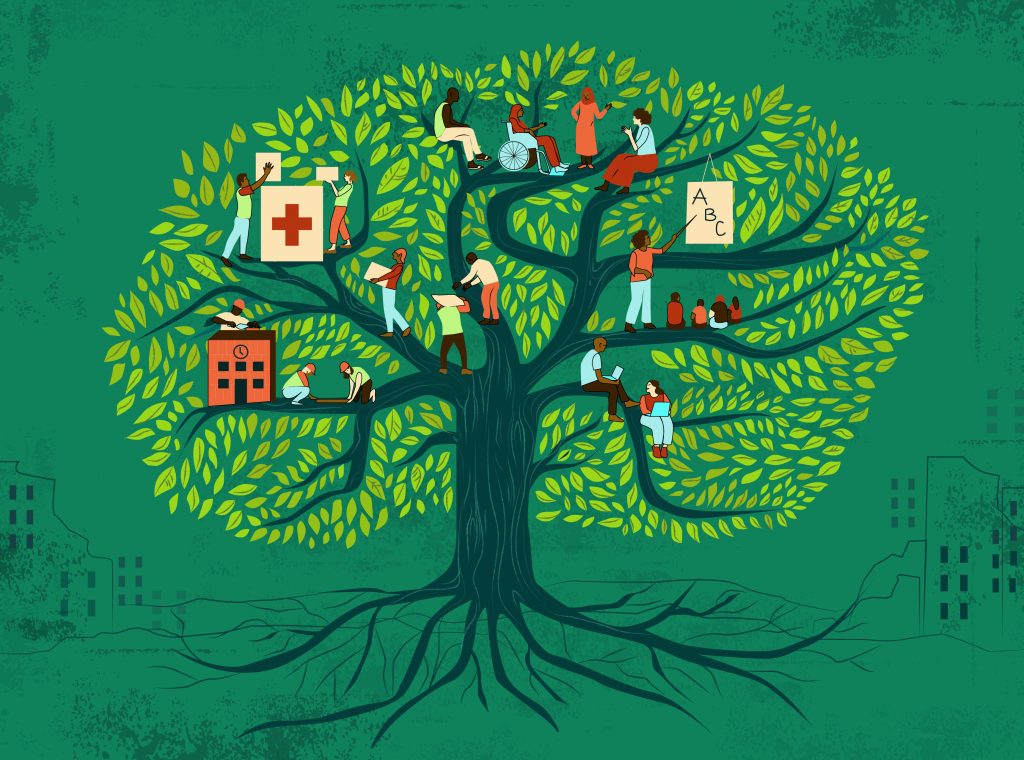

Imagine holding a rubber ball. You squeeze it, it bounces back. You squeeze it again, it bounces back once more, unchanged from before. That, in a nutshell, is resilience – an individual or a community’s ability to withstand and recover from shocks and stresses.

BUT IS IT ENOUGH for the ball to go back to how it was before? What if, instead of remaining the same, we could grow and improve after a shock?

Redefining resilience

That’s what we want to redefine as resilience: the ability of people, societies or systems to respond to shocks like natural disasters, war or economic crises by evolving into something more sustainable and more beneficial for all. Thus, next time a shock comes, the effect is significantly lessened, until it barely makes a dent. In the jargon we talk about replacing ‘absorption capacity’ with ‘transformation capacity’.

On FCA’s social platforms we often receive questions about how long we should go on helping during a crisis. At a time of global hardship, rising prices and multiple crises, these questions are louder and more frequent. Concentrating on building resilience through long-term development projects, can offer a solution. Although these projects often require a similarly long-term commitment, the results will ultimately reduce costs and, most importantly, suffering.

Did Covid reveal the resilience recipe?

The Covid-19 pandemic brought up many questions of resilience, especially in the healthcare sector, but also regarding the economy. Why were some countries more resilientce to the effects of the pandemic than other countries? Are there fundamental pillars of resilience that go to make up an intrinsic ability to withstand stresses better than others?

But defining or measuring resilience in this way is often not practical. While there are specific blocks of resilience that arguably help – a strong education system, economic diversity or strong government structures – other qualities are more abstract, like strong community ties or national identity.

Resilience can thrive even in fragile states

To start understanding resilience, we must also look at its different guises and check our assumptions. Resilience can be found on an individual level, a community level or within society at large.

Therefore, we can find resilience even in fragile states without robust national structures, when we look at resilience as more than just a strong economy and infrastructure.

“We often find there is a very strong communal resilience in places we work. Even though people have really little, if any one of the group is not doing well, the group will help. These are people who are by some measures very poor, but even within that context they would be able to help out each other. That’s absorption capacity,” says Director of Programme and Operations for the Network for Religious and Traditional Peacemakers, Matthias Wevelsiep.

Syrian communities showed resilience

Sometimes these different levels of resilience prop each other up, sometimes they step in to replace each other. For example, in Syria, some areas were able to function even with war all around, due to their strong social ties and community structures. Those structures came into play when we provided catch-up classes for children who had missed years of school. Word quickly spread and families were generally keen to send boys and girls to attend.

In a development context, when we’re considering a community’s resilience, we should also look past our assumptions to sources of resilience that may not be immediately obvious. Women and girls, as an example, are often naturally resilient, but may be being kept back by oppressive systems.

How do we support resilience?

Our first priority is to human life and dignity. But, when any organisation makes interventions, we should be careful not to change indigenous systems to make people less resilient. Rather, we must look, listen and learn to fully understand local contexts and what the UN calls a “Resilience Lens” to assess how our planned activities will strengthen institutions, contribute to sustainable benefits and contribute to social cohesion. In different contexts the same interventions will have significantly different outcomes.

We must also be aware that resilience and rights sometimes clash. For example, a young refugee entrepreneur finds a livelihood opportunity and starts earning a living by responding to local markets. From a rights perspective, that young person ‘should’ be in school, because they have the right to education. But to enforce that right could also run the risk of lessening that young person’s resilience.

“If we go in from a rights perspective we’d say ‘well, we need to change all of that’, but it’s a really long path in many countries to get to a level where everyone gets to school. So can we rather find a way to build on that resilience and find a solution,” suggests Wevelsiep.

Therefore, we can consider flexible projects, like programmes that offer a gradual entry into re-education, non-formal learning or, for older teenagers, linking learning to earning.

Societies cannot be put on hold during a crisis

Humanitarian work is rightfully often purely concerned with immediate needs and often doesn’t look at long-term resilience. But with that mindset, we will always be responding, rather than preparing. In areas where disasters are recurrent, anticipation is key, and it can’t wait for the current crisis to be over.

“If societies are put on hold for the duration of a conflict it means that right after the conflict you need a generation or two before you go back to what is normal. That’s why we need to work with, for example, teachers during a conflict so that they are prepared for when conditions improve,” explains Wevelsiep.

The example of education in emergencies, where access to schooling is prioritised up with other humanitarian needs, is significant. When responding to a disaster, we must always be looking at how societies will look after the fact. How will Ukraine look after the war? How will people in South Sudan return to their houses after flooding? What can we do now that can prepare the ground?

The UN has put forward a resilience-based approach, which focuses on a strengthened humanitarian-development integrated response, especially during prolonged crises where large numbers of refugees live amongst a host community for years. It’s found that programmes like providing livelihood opportunities for refugee and host communities are essential to levelling up resilience.

The climate crisis will test our resilience

One of the most obvious tests of global resilience is climate change. We are looking at each one of our projects, as well as our own organisation to mitigate, and build resilience to, the effects of rising temperatures.

“Ten years ago, even five years ago the climate crisis seemed far away, but now it’s real. Now our Country Offices see first-hand what is happening in Kenya, in Somalia, in South Sudan. They know the drought situation, the floods, the extreme weather events. For them it’s their reality,” says FCA Climate and Environment Sustainability Advisor, Aly Cabrera.

We are already developing better practices, like implementing circular economy projects, which cut out waste from the production cycle. An example is our BUZZ project in Nepal, which uses larvae from the Black Soldier Fly as animal feed, rather than traditional crops.

“The waste from the livestock is reused again and again for the larvae. It’s a really good initiative because there’s also a competition for food for human consumption and for animal consumption. With this you don’t have to have space to grow crop for animal feed and that also reduces practices like deforestation,” continues Cabrera.

Looking to the future

At FCA, we are looking at the future in our three areas of work to find out how we can promote resilience. In our peace programmes, we work with governments and civil society, as well as traditional and religious leaders to find out both the drivers of conflict and the opportunities for change. We’ve often seen that young people are sometimes surprise peace mediators.

“We find that young people are sometimes very well positioned to work on conflict, which is interesting because our assumption might be that young people wouldn’t have a chance, no-one would listen to them because society is age hierarchical. But then in facilitating local conflict resolution, it works because often they don’t own the history of the conflict, which frees them to be more questioning,” muses Wevelsiep.

Anticipating and adapting

Similarly in our education and livelihood work, we are anticipating the changing environments and adapting. In South Sudan, where extreme flooding is now the new normal, we are developing flexible and mobile learning spaces for schools to continue teaching. In northern Kenya, where conflicts are increasing over shrinking grasslands for cattle, we are introducing alternative livelihoods, while supporting local peacebuilding and conflict resolution groups.

However, we must never lose sight of the fact that the ultimate source of resilience is not what we bring, but the people we work with, something upon which Matthias Wevelsiep often reflects.

“Too often, even though we’re talking about empowerment, when it comes to our work, we too often look at people being vulnerable. While they may be in a certain sense vulnerable and their rights violated, that’s not the limit of who they are. I think that resilience and vulnerability are two sides of the same coin.”

Text: Ruth Owen