A school for the whole village

A school for the whole village

The annual Nenäpäivä (“Nose Day”) event in Finland collects contributions to support the education of teenage mothers, underage workers, and students with disabilities. In remote Ugandan schools, these funds are helping some students achieve even the highest grades on the scale.

DRUMS BANG OUT a rhythm as children dance and sing in the schoolyard. They are celebrating the beginning of a new school year at a remote school in Mubende, about 150 kilometres west of Uganda’s capital.

As the children celebrate, the whole village celebrates. A boy sitting by a tree in the yard takes up a cue from the adults, digs up a rectangular tin box and holds it confidently between his fingers. It is not only smartphones capturing this performance – it is also saved on the imaginary memory card of the box.

This Ugandan school used to be one of the worst performers in the Ugandan national competency test. Now, it is the specifically preferred option for an increasing numbers of parents. Its students’ grades and reading skills have improved dramatically, teachers are getting extra training and extra-curricular music, sport and drama activities are being organized for the children.

“Some of our students still have learning difficulties, but at least now us teachers have the tools to tackle these challenges,” says Mary Tuhirirwe, who has been a teacher at the school for 12 years.

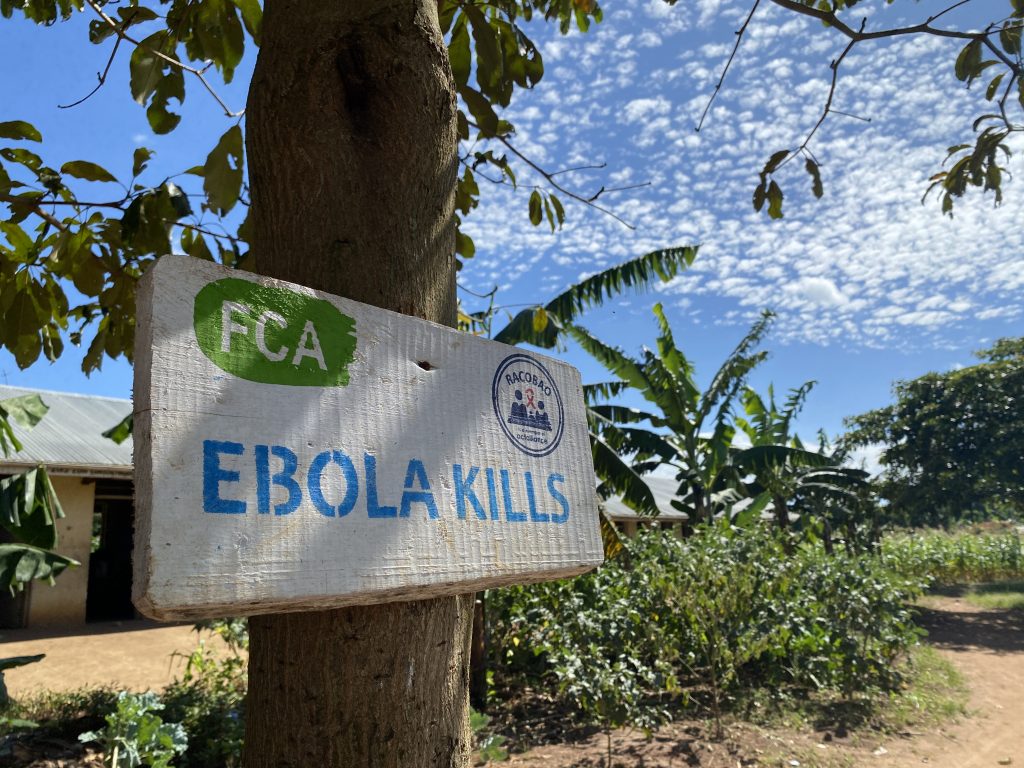

Finn Church Aid has been using Nose Day funds to support schools in Mubende since 2019. A key role has been played by Racobao, a local partner organization. In collaboration with the schools, Racobao has introduced what a crucial element to the mix: letting the whole village community to participate in helping.

COMPARABLE results have been achieved in a total of 20 Ugandan schools, many of which were often empty before the project. Sometimes even the teachers skipped school.

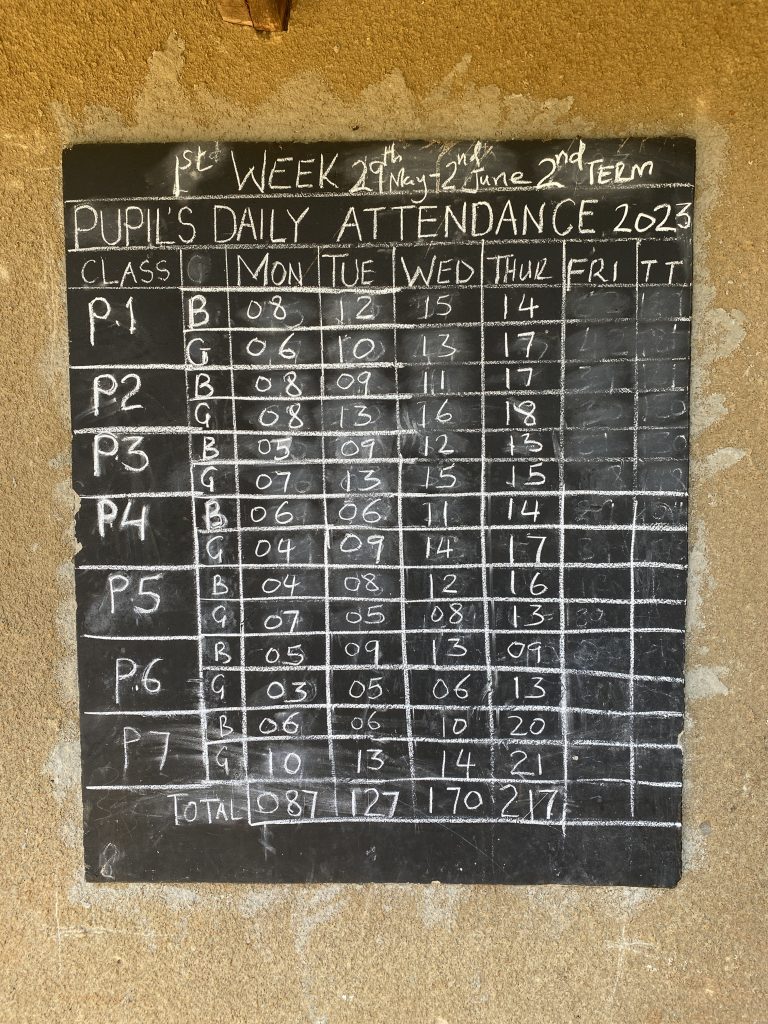

87 children attended on the first day at Mary’s school. It is not a substantial number in a school with over 500 pupils, but the teachers are not particularly worried yet. They know that the bean harvest is underway – that will keep many families busy for a few days more. Kids skipping the first few days of school to work in the fields is hardly a disaster, though Mary worries more about the children working in the nearby mine.

“I’ve been telling parents to put their kids to school – it’s always worth it. Yes, the work might get the child paid, but such money will be sent in an instant. Education, however, is an investment for a lifetime,” Mary Tuhirirwe stresses.

Around these parts, it is never self-evident that schools are even open at any given moment. Due to COVID, Ugandan children have endured a two-year school closure – the longest one in the world.

Mubende suffered another tragedy when Ebola started spreading in the region in late 2022, with the schools closing for months yet again. The school closures have had a transformative effect on the lives of many girls, with a significant increase in teenage pregnancies.

17-year-old Miriam (name changed) was 15 when she gave birth to a son. The father of the baby left the village after learning that Miriam was pregnant, offering no support to the young mother. Miriam tells us how she dropped out of school once her belly started getting bigger, and how sad it made her feel.

“My mom said I couldn’t go to school anymore, since I would be setting a bad example for the other children,” Miriam recalls. She is stroking her son’s head as he sits on her lap.

When Mary Tuhirirwe turned up in her backyard one day, Miriam’s world turned upside down.

“Madame Mary has come to talk about my sisters,” I thought. When I realized it was about how I could return to school instead, I was over the moon,” Miriam recalls.

Mary assured Miriam she would not have to pay school fees – just returning to school was enough. Miriam’s mother finally agreed with the plan, promising to look after the boy during school hours.

It is not easy, being a teenage mother in the countryside. The neighbors keep whispering behind her back and mocking the young mother. Many think Miriam is weird for choosing school over regular work.

“I have a child, but I also still see myself as a child. I want to educate myself and hope to have the skills to take on adult responsibilities at some point,” Miriam reflects. She offers advice to other teenage mothers:

“Pregnancy is not the end of the world, and you can always return to school after giving birth. I never regret being a mother, but still, once I grow up, I want to be a teacher – just like madame Mary.”

The interview ends with Miriam asking if she can leave home to go to school already. The day’s lessons are already in progress.

ALONGSIDE child workers and teenage mothers, teachers have also encouraged parents to ensure the education of children with disabilities. At another school, at the end of the red-sand roads, Joshua Kisakye attends classes. He is 6 years old but looks below his age and cannot move at all on his own.

When village teachers went into homes to encourage parents to send their children to school, Joshua’s mother Mariam Nakintu was exhilarated. Finally, something new to add to her son’s days.

“Joshua has been in school for a year with other children. He is no longer as shy; he no longer hides when there are other people visiting,” Marian says.

An outsider might not see much progress, but Joshua seems to respond by making noises when teacher John Twesiime teaches him the alphabet in class.

“Many parents keep thinking that children with disabilities don’t belong in school. Joshua is very special to me, though, and I try to create a learning environment where he can learn together with his peers.”

OTHER students at Joshua’s school have also benefited from the work supported by the Nose Day funds. There are more and more children attending school these days. Interaction between families and the school has improved, which in turn affects the whole village’s experience of community identity and its value.

Nisurunziza Bidas, a family father, is a member of the parents’ association, which actively promotes dialogue between the community and the school. The project’s start in 2019 saw a clear effect on the students’ grades. For the first time ever, schools in the Mubende district are seeing kids getting even the highest grades on the scale.

“Education is crucial. I have tried to get parents to put their children in school right from the first day on. Sure, my children have to housework to do in the evenings and during holidays, but when schools start, that’s study time,” says Nisurunziza Bidas, bluntly.

BY THE END of the first school week, more and more households have finished the bean harvest. One look at the blackboard of Mary Tuhirirwe’s school confirms this: 87 pupils came to school on Monday, 217 on Thursday.

Now the classrooms are full of joyful noise. It is lunchtime and the kids dig out the plastic cups they have brought with them. The cook pours a ladleful of corn gruel into each cup. Having school meals is a step forward in these parts in helping improve the children’s concentration. No-one learns well with an empty stomach.

Lean as it is, the whole community is chipping in to provide this corn gruel. Families have pledged to bring a few kilos of corn for the school’s common store for the semester. The teachers also cultivate fields, not only for the school but also for their own use. The extra income from cultivation is also needed by Mary Tuhirirwe, whose monthly salary is only about EUR 100. Mary also dreams of rearing pigs – but teaching is still her chief calling.

“Students’ behaviour has changed. They know their rights and possess more skills for doing different things. I can only hope this change can be maintained.”

Text and photos by Ulriikka Myöhänen