Finn Church Aid handed over the completed structures to the beneficiaries and local government in Bidibidi and Omugo refugee settlements.

A major improvement in the education of children and youth began with the opening of 34 newly constructed school blocks in Bidibidi and Omugo refugee settlements in Northern Uganda.

A major improvement in the education of children and youth began with the opening of 34 newly constructed school blocks in Bidibidi and Omugo refugee settlements in Northern Uganda.

FCA built 102 classrooms, 28 latrine blocks and 65 teacher houses with EU humanitarian funding to provide a conducive and safe learning environment to the vast number of children in the settlements.

The children celebrated the handover in separate ceremonies in the presence of government officials, UNHCR, refugee community representatives and parents.

Over 60 percent of the South Sudanese refugees are under 18 years old. Many have thus far struggled in temporary structures like tents that heat up quickly during sunny days, and are vulnerable to extreme weather conditions. The newly finished buildings are semi-permanent and safe.

In addition to the structures, FCA has trained 108 teachers in dealing with children in a crisis context. A total of 400 teachers are to be trained during the project. The teachers and child protection committees also received bicycles to support them in their roles in ensuring child protection in both schools and communities.

Read more about Finn Church Aid’s work in Uganda here.

The completed classrooms provide students with a safe environment for learning.

To address the high demand for teacher accommodation, FCA recently constructed an additional 25 tukuls for teacher accommodation across 5 schools in Bidibidi.

The Promise to Practice report gives recommendations on how to follow through on international commitments to support the future of Syria and the region ahead of the Brussels conference in late April. The report is signed by 39 agencies, including Finn Church Aid.

The conflict in Syria has created the largest displacement crisis in well over a generation, possibly since the second world war. Six million people remain displaced internally, more than five million are registered as refugees in neighbouring countries and over a million more have fled to Europe or elsewhere.

Click on the picture to download the full report.

Despite a moderate increase in return of mostly internally displaced people in 2017, the last year saw three newly displaced Syrians for every person who returned home. The recent escalations of violence in Idlib and Eastern Ghouta dramatically underline the point that Syria’s conflict, and the ordeal for its civilians, is far from over.

The international community has made significant financial and political commitments to address the massive scale of this crisis, in particular through two major conferences, held in London in 2016, and Brussels in 2017. A follow up conference will be held in Brussels on 24-25 April 2018.

Last year’s Brussels conference saw pledges of US$6 billion, and a further US$3.7 billion for 2018-2020. This funding has meant millions of people inside Syria can access humanitarian assistance. It has supported refugees and poor host communities, as well as the governments in neighbouring countries who have shouldered much of the response. It remains as vital as ever.

Furthermore, donors and host countries at these conferences adopted a “comprehensive approach” to responding to the refugee crisis. They made commitments to attempt to ensure refugee families and the poor communities that host them can access work and education.

These commitments aimed to create 1.1 million jobs in the region, for example, and ensure all refugee children were in school by the end of the last school year. They subsequently recognised the importance of giving refugees legal protection in order to achieve these goals, and the need for resettlement of vulnerable refugees and other safe and legal pathways beyond the immediate region.

Yet, as the Syrian crisis enters its eighth year, the lives of many of the five million refugees in neighbouring countries have seen little improvement, and the number of refugees offered resettlement has actually fallen since the commitments made last year.

This report details the commitments made in previous years and tracks their implementation. It then offers specific recommendations for those gathering this year for the second conference on “Supporting the Future of Syria and the Region” in Brussels, to ensure the ambitious and comprehensive approach is translated into real changes in the lives of refugees and vulnerable communities in Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey.

The stakes are high: failure to follow through on or properly fund these commitments would carry serious consequences, including many people returning to Syria before it is safe to do so.

Importantly, 39 aid agencies and 3 interagency bodies call on the conference to reaffirm that the conditions for the safe, voluntary and dignified returns of refugees, in accordance with international law, are still not in place.

We also call on participants to agree to an accountability mechanism, based on international best practice, to ensure that the necessary funding pledges are disbursed and the ambitious policy pledges committed to at the first Brussels and London conferences are implemented.

Download the full report in pdf format from this link. Read more about FCA’s work in Jordan here and in Syria here.

There are anniversaries for humanitarian workers that are sad reminders of evil in the world. This week marks the seventh year of the Syrian war, and this is no cause for celebration. There is just a cruel war in which all parties have lost a long time ago.

Last week, I was in Syria for a project monitoring trip, and the war was constantly present. The war could even be seen in areas that have not had violent conflicts. In addition to visible fights, 6.1 million internally displaced persons place a burden on the economy of more peaceful areas and on public services.

The war affects the life of every Syrian.

During my trip, I met with colleagues over breakfast in the mornings, and I listened in silence as they talked about the friend or relative in Damascus whose house had been hit by a rocket and whether anyone had been killed or injured. I was shaken by how everyday these stories sounded coming from them and how tired they are after seven years of war.

We were supposed to go to Damascus, but it is impossible at the moment. The fighting in Eastern Ghouta is at its most heated, and dozens of rockets and grenades are fired at the city every day. On my last visit in the fall of 2017, the streets were full of people in the evenings. Single projectiles did not hold people back. Now, in March, people think it best to stay at home.

The Syrian war is a shameful example of the failure of great powers

As humanitarian operators, we do not publicly take sides in politics, but I have to say that seven years of war in Syria is a shameful example of the failure of political will and decision-making on the part of great powers. In the midst of this political tug-of-war, the one to suffer most is always the human being, whichever side of the front line he or she lives.

The victim has been an entire nation, especially children. There is a whole generation of refugees in Syria’s neighbouring countries that has never lived in their native land. At Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan, 80 Syrian children are born as refugees every week. They grow up within the walls of refugee camps and in the poor quarters of a foreign land.

Seven years have left behind unimaginable destruction and human suffering. Hundreds of thousands have died, and in addition to internally displaced people, 5.6 million refugees have fled to neighbouring countries. The real number is much higher, since not everyone has been registered.

There are glimmers of light in Syria, as some get to return to their homes and are able to restart their lives. However, the overall situation for civilians is worse than ever.

69 percent live in extreme poverty. The price of food is eight times higher than before the war. 5.6 million people live in a life-threatening situation, without shelter, protection, and unable to meet fundamental rights or basic needs.

These people are in need of immediate humanitarian aid, and fast, but it cannot be easily delivered everywhere, as is the situation in Eastern Ghouta right now.

Functioning washrooms mean more pupils

Muqlos school in rural Homs in October 2017 (left) and after the rehabilitation in March 2018. Photo: Olli Pitkänen.

Finn Church Aid has supported children’s opportunities for going to school and the restoration of school buildings since 2015. Even though children’s access to school has improved in recent years, 1.7 million school-aged children, or 43 percent, are still out of school.

The need to get children to school is enormous in both Syria and neighbouring countries.

This winter, Finn Church Aid supports the restoration of 12 schools in central Syria. Classrooms, washrooms, and water stations are renovated, walls are painted, and desks are repaired.

Washroom and toilet of Muqlos school in rural Homs area in October 2017 and in march 2018. Photo: Olli Pitkänen.

We visited ten schools, and many children of internally displaced people study in each of them. At the Tartus countryside, principal of Muniat ya Mor school Hamsa Ali says with gratitude that renovating the school meant a lot to the community.

”Before, the toilets did not work and there was no water. Now they are in really good condition. The renovated school facilities have lured the children back to school,” said Ali during my visit.

Joyful colours on the classroom walls have already improved learning results. Absences have dropped, and fewer children and young people than before drop out of school. Teachers’ motivation has improved.

Teaching and learning are appreciated again!

Yusra Naser school in Safita has 361 pupils, 81 of whom the children of internally displaced people. English teacher Lucy Vitar believes there is a bright future ahead for the students.

”They are sad because of the war. Many of them are really bright, and we hope that they learn to love studying,” says Vitar regarding the significance of the renovation work.

Maintaining hope is important everywhere. The desire to believe in a brighter future makes people work for the common good. This could be felt in all the schools.

Principal of Nadim Resla school in Latakia, Fateer Barhom, summed up the effects of the seven years of war in a way I found apt. Although the war has affected everyone, adults need to be able to take responsibility for the children and create the best possible circumstances for them to study in.

Children deserve a chance to build their life in a safe environment.

Olli Pitkänen

Development Manager, Middle East, FCA

The office of principal Noura in Muqlos school in October 2017 and March 2018. The reconstruction of schools gives hope of a brighter future and motivates also the teachers. Photo: Olli Pitkänen.

The greatest fear of Muja Rose, a refugee from South Sudan, is that her daughter will starve to death. Uganda is at a breaking point in the throes of the biggest refugee crisis in Africa since the Rwanda genocide.

The children were playing when war found the family of 34-year-old Muja Rose in South Sudan.

Government soldiers arrived without warning in their hometown of Kajo Keji. They were immediately caught by surprise by a group of rebels. People were killed and their possessions were looted.

Rose’s husband was away, and in the crossfire, Rose made the toughest decision of her life.

”The only alternative was to run as fast as my feet would carry. I decided to take the children to Uganda,” says Rose.

Rose managed to take her own four children as well as two children who had lost their mother with her. She carried the youngest one on her back through the bush and stayed up all night to protect the children from wild animals. They had no food or water.

”The children were crying out of hunger and exhaustion. When we found a dry streambed, I tried to dig for water in the ground to have drinking water for the children.”

Food is a constant preoccupation

A year later, all the children are seated around a clay oven in the Bidibidi refugee settlement. The area, the size of Turku, has 290,000 inhabitants, which would make it the second biggest city in Finland after Helsinki.

The clay oven is located in the only shaded spot in the yard, and attracts others to seek shelter from the relentless sun. The aroma from the sizzling pot is familiar from any kitchen in the world: fried onions.

Rose chops a few eggplants from her vegetable garden and adds them to the pot, with 10-year-old Ayite stirring the stew.

”Once a week we cook eggplants, once okra, once vegetables. The remaining days we eat beans,” says Rose.

”The food has no variety and the children are sick all the time. They’re not getting all the vitamins they need.”

Food is constantly on Rose’s mind. Even though the demanding journey to Uganda has reduced the risk of becoming victim to bullets or rape, life is a taxing struggle to meet basic needs. She is not alone in this situation.

Over a million people from South Sudan have crossed the border to Uganda, almost all of them after July 2016.

Some refugees are lucky to have chicken that produce eggs. Most, like Muja Roses family, have left behind all their possessions when fighting broke out. Photo: Tatu Blomqvist

Taking care of the crisis costs about 560 million euros per year, but the international community has only met a third of the need. According to the UN, Uganda is at a breaking point. The refugees most feel this in the food rations that have been halved twice, says Bik Lum, regional head of UN refugee agency UNHCR.

The food aid delivered monthly includes beans, vegetable oil, salt, and maize meal. At the end of last year, the maize meal rations were cut from 12 kilos to 6 kilos per person.

”Some have risked their lives and gone to South Sudan to look for food in their abandoned homes,” says Lum.

One meal a day

Uganda, a country smaller and poorer than Finland, has despite its limited resources admitted all refugees into the country.

The Ugandan refugee policy is praised as forward thinking in the western world, since among other things, it guarantees everyone a piece of land to live on and cultivate. This does not mean that life in refugee settlements feels meaningful.

More land has continuously been cleared from previously unliveable bush, and growing things to eat is hard.

Rose’s yard is rocky, but as a woman with green fingers, she has managed to grow something. So has Wani Garanep, living in the neighbouring village, who participated in Finn Church Aid’s (FCA) cultivation training.

FCA has provided participants with seeds and tools. Sesame, okra, and tomatoes are growing next to Garanep’s clay hut. Since the ground is rocky, Garanep and his wife Kaku have learned to fill sacks with dirt. Onions and eggplants are growing in these sacks.

Wani Garanep’s family has managed to diversify their diets with vegetables after participating in FCA’s livelihoods training. Photo: Tatu Blomqvist

However, because of slashed food rations, the family has been forced to cut their daily meals from two to one. This goes for most of Bidibidi’s inhabitants.

”I would like to guarantee a good education for my children, but they can’t concentrate in school when they’re hungry, and they often come home before the school day is over,” says Garanep.

Garanep is a builder by trade. In South Sudan, he cut down trees and sold them as building material. The family could afford to eat meat.

Rose worked as a teacher, and the family had no shortage of food.

The hometown she left behind, Kajo Keji, was located in Equatoria, the breadbasket of South Sudan, known for its fertile soil. Before the war, the region was able to feed millions of people. Rose’s family had goats and chickens.

”When the children were hungry, they would pick fruit or cassava from our garden,” she says.

However, Kajo Keji is empty. Three quarters of the population of Equatoria have left their homes and Northwest Uganda is like one big refugee settlement that it takes hours to drive through.

Here, Garanep and Rose find it hard to find work with which to improve their families’ situation.

”Sometimes when the children are really hungry, they ask me ’mom, can’t we go back home to South Sudan so that we could eat.’ It’s hard to explain to them that there is still a war going on there,” continues Rose.

Life as a single parent is tough

After the meal, things get more active in the yard. With 13-year-old Gire and 9-year-old Diko in the lead, the children dig out a skipping rope. With great enthusiasm, Ayite counts her skips in English. This makes her mother happy.

They are more eager than usual because there are visitors, she explains. When the children are quiet and too tired to play, it is time to worry, she says.

Gire and Diko are not Rose’s own children, but after their flight together, they sleep together with Rose’s children.

”Sometimes they ask me where their mother is. Once the war is over, we will return to look for her.”

Life as a single parent is especially hard in the refugee settlement. Over 60 percent of the refugees in Uganda are under 18 years old, and most of the adults are women. When women and children fled, men took part in the fights – some forced, others voluntarily – or died in the conflicts.

In Rose’s yard, it is evident that she has to keep an eye on more than a dozen children, with barely no other parents in sight. Rose often worries about how long she will manage if the situation is prolonged.

”I miss my husband. I don’t know whether he’s alive or dead. I haven’t heard from him since we had to run away,” she says.

During the interview, Rose mends the trousers of her youngest child, 3-year-old Wani. They have to be taken in at the waist once again. Rose is most worried about 10-year-old Ayite, who has gone down from 25 kilos a year ago to just 19 kilos.

Being underweight makes Ayite vulnerable to disease and malnutrition.

”If she loses more weight, I might even lose her,” says Rose.

Text: Erik Nyström, photos: Tatu Blomqvist

This year, 60 percent of the funds collected in the Common Responsibility Campaign are directed to the Finn Church Aid disaster fund. Read more about FCA in Uganda here.

President Tarja Halonen got an enthusiastic reception from refugees at Za’atari camp in Jordan. With her visit, she wanted to show her support to FCA’s work with Syrians.

Girls’ football practice electrifies when Tarja Halonen shows up at the edge of the field. A female president is not a common sight in the Middle East, and the girls want to show their skills to the best of their abilities.

The refugees at Za’atari have hardly ever taken so many photos of a visitor.

”When an eight-year-old refugee girl gets to play football at a refugee camp and realises she is as good as her brother, what an effect it has on the girl’s self-esteem,” Halonen muses.

”I hope her future is good as well.”

The girls wanted to impress the visitors at the FCA football field at Za’atari. Photo: Mohammed Barhoum.

On Tuesday, Halonen visited the Za’atari refugee camp in the middle of the Jordan desert. The purpose of the journey was to update the president’s knowledge on the Syrian refugee situation and to support Finn Church Aid’s (FCA) work for her part.

Chair of FCA board Tarja Kantola and Finnish ambassador in Beirut Matti Lassila joined her.

The camp, founded six years ago, has almost 80,000 refugee inhabitants, and although new refugees are no longer admitted, the population grows with 70 to 80 newborn babies every week. FCA’s operation at Za’atari began in early 2013. FCA has become famous at the refugee camp with projects such as its circus school, with acrobats and clowns making an impression on Halonen as well.

In addition, the president visited courses on English, music, and information technology. The hairdresser course students would have loved to cut and sculpt the hair of Halonen and those in her group into completely new shapes.

Halonen considers it important to continue offering education and hobbies.

”The education, employment, and hobbies offered by FCA has a significant impact on the refugees’ self-esteem, and they should therefore continue,” she says.

Finnish businesses could help in crises

It is becoming increasingly hard to secure funding for a refugee crisis. Halonen finds it sad that funding for non-governmental organisations has decreased significantly in Finland. Even though politicians have stressed in speeches that the situation should be handled on location, necessary funding has not been granted. Furthermore, Finland should not return asylum seekers to their countries of origin, if the requirements for a decent life do not exist.

In Za’atari, Halonen also sees lots of opportunities for Finnish businesses to create innovative solutions to improve camp conditions. As an example, she brings up accommodation containers in which families are living.

”The containers are cold in the winter and hot in the summer. Would Finnish wood structures have a niche in accommodating refugees as well,” she muses.

”Finnish businesses are often too cautious and too prejudiced in marketing themselves in a crisis region.”

At Za’atari, people both live and work in construction site containers. In the photo, Tarja Halonen visits an English class for children and youth. Photo: Mohammed Barhoum.

Syrians have already started to return to Syria from Jordan, but according to the UN, returning is not safe. The war has gone on for almost seven years, and the infrastructure of the country is in shambles. Fighting is still going on across the country. In recent days, the UN and international organisations have expressed their shock over the bombing of civilians in eastern Ghouta.

The message of the refugees in their encounters and photos with the president to everyone in Finland was: don’t forget about us.

”We should be offering the refugees light and warmth,” says Halonen.

Text: Olli Pitkänen Photos: Mohammed Barhoum

The author is the FCA Regional Programme Manager of the Middle East.

Read more about FCA’s work in Jordan here.

The students of the circus school arranged a performance to honour the president’s visit. Photo: Mohammed Barhoum

Tarja Halonen follows eager barber students at their work. Photo: Mohammed Barhoum.

FCA and the European Union construct 28 blocks of 84 classrooms, 28 blocks of 140 stances of inclusive gender-segregated pit latrines and 40 teachers houses in Bidibidi and Omugo refugee settlements to ensure a safe and inspiring learning environment for South Sudanese refugees.

The cheers from Para elementary school travel a great distance from the schoolyard. Classes finish at 16.00 and the children from grades 5 and 6 are on their way home.

After a day of intensive learning, their minds are

set on future goals. A group of seven friends do not need much time to consider their favourite subjects, when asked. The answer is science and math.

“I want to become an engineer, so that I could for instance design and implement a water supply system at the refugee settlements”, says 16-year-old John.

Same-aged Mary would consider a career as an accountant because she likes to play with numbers, while Emmanuel, 17, longs to be a pilot or driver because he wants to explore the world.

16-year-old Scovia reminds that English is important whatever your dreams might be.

“I would like to become a nurse so that I could help sick people”, she adds.

Additional semi permanent classroom at Para Primary School.

21 000 pupils benefit from improved access to quality education

Over 60 percent of the arrivals from South Sudan are children under 18 years old. When arrivals peaked following the eruption of violence in Juba in 2016, it took months for most to continue their education in Uganda. Temporary structures, primarily tents, were set up in the settlements to meet the urgent needs.

Today, children usually resume their studies within days after their arrival, and efforts have focused on upgrading the temporary structures to semi-permanent classrooms of concrete from which refugees benefit. The tents are hot during summers and vulnerable to extreme weather conditions.

FCA is set to complete 28 blocks of 84 classrooms by January 2018 with EU humanitarian funding. The cooperation improves the learning environment in 7 schools in Bidibidi, one of the world’s largest refugee settlements and 6 schools in Omugo settlement, established in August. When finished, FCA’s and the European Union’s project will immediately benefit around 21 000 pupils.

At Para Primary School, the first two blocks of six classrooms and one block of latrines are finished, and the last part of the construction is well on its way.

“The learning centres are established with a high priority not only because of the importance of education, but as a safe space for children and youth”, Denis Okullu, coordinator of the project explains.

Training of teachers key to learning

The cooperation between the European Union and FCA also extends to the teachers, who have more than 1 500 pupils to care for at Para Primary School. One essential training of Teachers in crisis contexts addresses the challenge in dealing with such a large number of students.

“We use a lot of group work and working in pairs in order to manage the situation”, Andero Kasifa says.

A total of 237 teachers are to receive the training and Kasifa is one of them. The project also works on accommodation for the teachers, prepares them for work with children in a crisis context as well as involves parents in supporting a safe and productive learning environment.

Especially children who have been years out of school require attention in order to get back on track. A placement test decides their initial level, and through a process of accelerated learning, they can catch up and complete for instance three grades within one school year.

“The skills we learn help us to help them complete their primary level education”, Kasifa says.

Additional classroom under construction in Luzira primary school with funding EU humanitarian funding.

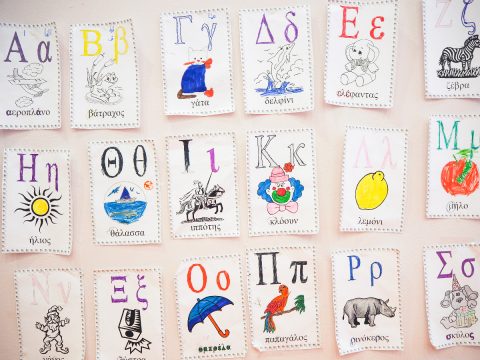

The coding workshops aim to facilitate the employment of young people with refugee or Greek background, and to increase dialogue between different groups in Greece. The pilot stage carried out in early summer garnered excellent results.

In November, Finn Church Aid starts workshops in Greece together with Greek NGO GFOSS – Open Technologies Alliance, aimed at young refugees and Greeks, teaching skills such as the basics of programming, robotics, image editing and other IT skills. The workshops, called Code and Create, are aimed at young people aged 15 to 24.

“Greece has the highest youth unemployment rate in Europe, and gaining access to the job market is challenging both for young Greeks and especially for young people with refugee background. Many refugees between 15 and 24 years of age have arrived in Greece alone, and they lack both networks and compulsory education. They are very vulnerable,” says FCA’s Greece Country Director Antti Toivanen.

The coding workshops were piloted in May and June, with 40 young people with Greek or refugee background participated in workshops organised by Finn Church Aid and and local partner organisation GFOSS.

“The experiences from the pilot were excellent, and the young people were excited to learn new skills. The workshops became real meeting places where many young Greeks and refugees got to know each other for the first time and even became friends.”

The workshops particularly aim to reach young people with no other way to learn skills that can be a great help in life and in succeeding at work. The participants are not required to have previous experience of programming, all that is needed is the basics of English and a motivated attitude.

The project is meant to continue until next summer. The target is to have 700 young people take part in the workshops. The participants are selected based on applications.

“Finn Church Aid has lots of experience of making use of Finnish education know-how in countries with challenging circumstances. Our aim is to offer the young person participating in the workshops better opportunities for further education or employment,” says Toivanen.

The workshops are led by GFOSS who have expertise in open source and open data. The curriculum is honed together with Finnish pedagogues to be learner-centered, and different learning models are employed in the classes.

“In the current refugee situation facing Greece and the whole Europe, we think it’s important to find new ways to support integration and interaction between people. Learning to code is a smart way to bring young people together,” says Toivanen.

There are currently about 20,000 refugees and asylum seekers under the age of 18 in Greece. Many of them have no access to a Greek school or other education. In a country which is struggling with a financial crisis which shows no signs of abating, even those born in Greece have found it hard to find employment or education opportunities. Over 47 percent of young Greeks are unemployed.

Despite increasing attention to the severe refugee situation in Uganda, the international community has done little to ease the crisis as it reaches a grim milestone. This is what’s going on.

1. Uganda is home to more refugees than any other country in Africa

With 1,3 million refugees by August 2017, Uganda hosts one of the largest refugee populations in the world. The reason behind the severe influx is the conflict in South Sudan. Each day an average of thousands of refugees have crossed the border to Uganda since fighting re-erupted in the capital Juba in July 2016. Within the region, Uganda has received the highest number of South Sudanese refugees, now one million.

The number of internally displaced people included, four million South Sudanese have left their homes, and this makes it one of the largest refugee crises globally. Only Syria and Afghanistan are producing more refugees.

2. An overwhelming majority of the South Sudanese refugees are women and children

More than 85 percent of the South Sudanese refugees in Uganda are women and children, who have traveled by foot to escape a devastating civil war. According to their stories, adult males – brothers, fathers and husbands – have been killed, captured or recruited by armed groups. Opportunities for education and livelihoods are therefore extremely important for this refugee population.

61 percent of the South Sudanese refugees who have arrived since July 2016 are children under 18 years old. Having access to protective and quality education is an essential part of the rehabilitation process for these children whose childhood has been cut short through horrific experiences while fleeing their homes. The provision of education to these children does not only give them hope for a better future, but it also affirms them that their futures are worth believing in.

3. Uganda is at a breaking point

Uganda has one of the most progressive refugee policies in the world. After registration, refugees have the right to study, work, set up enterprises and move freely within the country – all the same rights as native Ugandans apart from the right to vote. Refugees also receive a plot of land at the refugee settlements for cultivation.

But Uganda is also one of the world’s poorest countries. The pace of arrivals has been tough to keep up with, and the UN has warned that Uganda is at a “breaking point”.

4. Uganda needs international support to maintain its transformational refugee policies

Uganda needs the support of the international community to keep . The UN Refugee Agency UNHCR says it needs around 570 million euros to ensure minimum humanitarian standards are met properly, but this far it has received only 17 percent of it.

The funding gap delays projects like providing permanent shelters by months and people are vulnerable to changing weather conditions. Children attend schools in temporary tents, easily taken down and destroyed by high winds and rains. Food rations have been cut several times and creating new plots for farming is an enormous task as new settlements open.

Text: Erik Nyström

Finn Church Aid supports education and livelihood opportunities for refugees in Uganda. Read more about our work here. Read an interview with Uganda’s refugee commissioner here.

Because of war and having to flee their home, many refugee children have spent years without education. For many of them, learning centres aided by Finn Church Aid are the only chance to get to study in Greece.

Once in the corridor, children’s voices can be heard. It is impossible to make out the language, but the volume rises in the tiny hall behind a door on the top floor. Children are running around, and mothers are seated on the sidelines, waiting for their turn to talk to social worker Stella Paziou.

Monday is always a busy day for Paziou, as it is the day when new pupils are registered in the Athens-based Satovriandou learning centre. For many refugees and immigrants having arrived in Greece, places such as this centre are the only chance to get to learn, since integrating refugees into the Greek school system is still a work in progress.

It is Paziou’s job to learn about the children’s schooling history, and if necessary, to tell parents where they can find the services they need. She then directs the new pupils to a suitable group in which they begin to study Greek, English, and skills necessary to survive in the new country.

”The children may have a gap of several years in their studies, as they have travelled a long way to Greece, and many may have had to drop out of school while still in their home country because of war,” says Paziou.

The youngest in the centre, around three years old, attend the centre’s kindergarten. The oldest are on the verge of adulthood, and the centre also organises language courses for the pupils’ parents.

Over the course of a day, up to more than 100 children and young people visit the centre.

Language barrier has to be crossed every day

Finn Church Aid aids education of refugee children and young people in Greece

- More than 3,100 or about 15 percent of young refugees living in Greece have had the chance to study in Greece thanks to the work of Finn Church Aid.

- Finn Church Aid has aided its Greek partner organisations, Apostoli and Elix, e.g. by drawing up curricula for refugees and by training teachers.

The rooms of an old house have been divided into classrooms using low screens, and the murmur of voices from the adjacent classroom is carried into Natassa Tseliou’s classroom, with ten children furiously colouring various fruit.

”Fráoula”, says Tseliou in Greek, pointing at a picture of a strawberry.

”Al-Farawila”, repeats the assistant teacher in Arabic.

Teaching is challenging, as new pupils join the groups every week. Every time, the work begins from scratch; the teachers need to figure out what level the child is on and explain what schoolwork is about.

”In an ordinary school, education is directed at different ability levels, but here every child is on his or her own level. Some of the children don’t know any Greek words, or they may know words such as water that they needed at refugee camps in the Greek archipelago,” says Tseliou.

In the kindergarten, a snack is being served, and hummus-and-cucumber sandwiches disappear fast from a cardboard box. Kindergarten teacher Dimitra Kanata strokes the head of a little girl who has stopped to hug her leg.

”Every day, we need to figure out ways to cross the language barrier, although we try to do as much as we can in Greek. We read stories and do craft projects based on them, the last thing we did was draw an ocean with fish in it,” says Kanata.

At Satovriandou learning centre, pupils are taught the basics of Greek, English, and their own native language. Photo: Noora Jussila / Finn Church Aid.

Finn Church Aid helps draw up curricula

Even though the Greek aid organisation Apostoli maintaining the centre has been carrying out aid work for a long time, the workers had no previous experience of working with refugees and immigrants. So, Finn Church Aid was called in to help.

”No child should be left without an education. Finn Church Aid has experience of education projects and working with people from different cultural backgrounds, and this collaboration has been a great help in drawing up curricula, for example. In addition, the volunteer from the Teachers Without Borders network has been a great help for our teachers, many of whom are newly graduated,” says Apostoli director of programmes Vassi Leontari.

The aim is to teach the pupils at Satovriandou centre enough Greek for them to study in a Greek school, or enough English for them to manage in other parts of Europe.

”We can see a clear change in the children once they get to study. Studying gives them faith in the future,” says Leontari.

Text and photos: Noora Jussila

The project is implemented in cooperation with UNICEF and supported by ECHO and Church of Sweden.

Teacher George Kalewis slams his hands on the table, and a little orange robot car nudges forward. We are in Athens, and a group of young people has just coded the robot’s sensors to react to sounds.

“Good work! Next, we’re going to code the robot car to detect a black line and to follow it. Does anyone need help?” Kalewis asks, and Michalis Vamvakaris, serving as assistant teacher for the day, circles around helping students.

In about fifteen minutes, everyone is done, and Kalewis moves to the driveways spread out on another table.

“Wow!” marvels Sofia, 17, when her car starts moving on command and obediently winds along the black driveway, all by itself.

Sofia is one of 40 young people taking part in the Code+Create workshops organised by Finn Church Aid in Athens from May to June. In addition to robotics, the workshops held once a week have focused on learning skills such as the basics of coding, image editing and 3D printing. Half of the participants are of Greek origin, while the other half have a refugee background.

“I already knew some of the basics of (programming language) Python, but here I’ve had the chance to learn much more in-depth. I think it’s wonderful that the group includes people with all sorts of backgrounds, because it’s good to get to know new people,” says Sofia.

Said, 18, agrees that it has been nice to make new friends. He arrived in Greece with his parents and six siblings a year ago from Afghanistan, where the life of the family had become too dangerous. They meant to continue to Germany where they had relatives, but their journey was cut short and they remained in Greece, where the family now awaits an asylum decision. At first, Said did not know anyone in Athens.

“It’s been hard getting to know Greek people, since not everyone speaks English. I’ve now started a Greek course at the summer university. When I heard of this programme, of course I wanted to join in. I enjoy studying very much.”

“Said, come here!” calls Michalis, 14, who lives outside Athens.

“It’s been great to get to speak English. At first I was shy, and my English wasn’t very good, but now it’s going well. It’s a good idea to include people from different backgrounds in the group. It helps us all to learn about new cultures,” says Michalis.

Michalis (on the left) and Sofia from Greece and Said from Afghanistan have become friends in the coding workshop. Photo: Socrates Baltagiannis

Language posed the first challenge for the teacher as well, as the IT terminology, complicated enough as it is, was not familiar to everyone. At first, the group learned to make use of online translation programs, but after that, the students have been unstoppable.

“The most rewarding part has been seeing how eager the young people are to learn. As the course progresses, they’ve become much more confident,” says Kalewis.

As his day job, he teaches robotics at a Greek university. Initially, he was a little nervous about teaching young people from different backgrounds, but he soon learned that he needn’t have worried. The young people got to know each other, and according to Kalewis, they are now like one big family.

“The youngsters from Greece now find it easier to understand those from different circumstances. They are all young, but they come from different countries. The most important thing I can teach them is not robotics; it’s ethics.”

The break over, Kalewis calls the group together again. Sofia, Said and Michalis get seated next to each other.

“Pay attention. We are now going to teach the robots to communicate with each other. We’ll turn some of the robots into receivers and others into transmitters,” Kalewis introduces the task.

The group follows closely. They all know much more about receiving messages from others than they did when the workshops started a month ago.

Teacher George Kalewis believes that young people from different backgrounds will understand each other better after the coding workshops. Photo: Socrates Baltagiannis

Text: Noora Jussila

Translated by: Leena Vuolteenaho

Code+Create workshops are organised by Finn Church Aid together with Greek NGO GFOSS – Open Technologies Alliance.

A major improvement in the education of children and youth began with the opening of 34 newly constructed school blocks in Bidibidi and Omugo refugee settlements in Northern Uganda.

A major improvement in the education of children and youth began with the opening of 34 newly constructed school blocks in Bidibidi and Omugo refugee settlements in Northern Uganda.